Guidelines for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles

| Creators: |

Karen Coyle

Consultant Tom Baker DCMI |

| Date Issued: | 2009-05-18 |

| Latest Version: | https://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/profile-guidelines/ |

| Release History: | https://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/profile-guidelines/release_history/ |

| Description: | This document provides guidelines for the creation of Dublin Core Application Profiles. The document explains the key components of a Dublin Core Application Profile and walks through the process of developing a profile. The document is aimed at designers of application profiles -- people who will bring together metadata terms for use within a specific context. It does not address the creation of machine-readable implementations of an application profile nor the design of metadata applications in an broader sense. For additional technical detail the reader is pointed to further sources. |

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Framework for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles

- Defining Functional Requirements

- Selecting or Developing a Domain Model

- Selecting and Defining Metadata Terms

- Designing the Metadata Record with a Description Set Profile

- Usage Guidelines

- Syntax Guidelines

- Appendix A: Description Set Model (from DCMI Abstract Model)

- Appendix B: MyBookCase Description Set Profile

- Appendix C: Using RDF properties in profiles: a technical primer

1. Introduction

When it comes to metadata, one size does not fit all. In fact, one size often does not even fit many. The metadata needs of particular communities and applications are very diverse. The result is a great proliferation of metadata formats, even across applications that have metadata needs in common. The Dublin Core™ Metadata Initiative has addressed this by providing a framework for designing a Dublin Core™ Application Profile (DCAP). A DCAP defines metadata records which meet specific application needs while providing semantic interoperability with other applications on the basis of globally defined vocabularies and models.

Note that a DCAP is a generic construct for designing metadata records that does not require the use of metadata terms defined by DCMI [DCMI-MT]. A DCAP can use any terms that are defined on the basis of RDF, combining terms from multiple namespaces as needed. A DCAP follows the DCMI Abstract Model [DCAM], a generic model for metadata records.

A DCAP includes guidance for metadata creators and clear specifications for metadata developers. By articulating what is intended and can be expected from data, application profiles promote the sharing and linking of data within and between communities. The resulting metadata will integrate with a semantic web of linked data [LINKED]. To achieve this it is recommended that application profiles be developed by a team with specialized knowledge of the resources that need to be described, the metadata to be used in the description of those resources, as well as an understanding of the Semantic Web and the linked data environment.

The interoperability of DCAP-based metadata in linked data environments derives from its basis in standards:

- Resource Description Framework (RDF), the foundation standard on which domain standards rest [RDF].

- the Dublin Core™ Abstract Model, a generic syntax for metadata records [DCAM],

- the Dublin Core™ Description Set Profile, a constraint language for Application Profiles [DCSP]

- DCMI guidelines for implementation encodings [DCMI-ENCODINGS],

2. Framework for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles

A DCAP is a document (or set of documents) that specifies and describes the metadata used in a particular application. To accomplish this, a profile:

- describes what a community wants to accomplish with its application (Functional Requirements);

- characterizes the types of things described by the metadata and their relationships (Domain Model);

- enumerates the metadata terms to be used and the rules for their use (Description Set Profile and Usage Guidelines); and

- defines the machine syntax that will be used to encode the data (Syntax Guidelines and Data Formats).

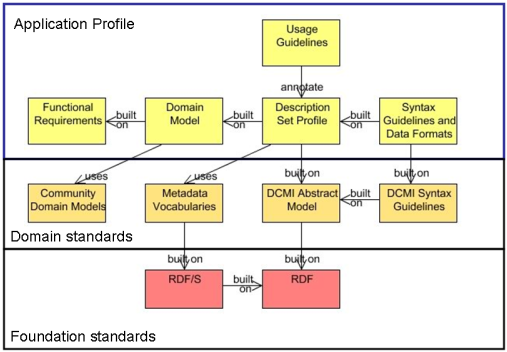

Singapore Framework

How these standards fit together is illustrated in the Singapore Framework for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles [DCMI-SF]. The bottom tier, RDF, provides the foundation standards on which domain standards are built. The middle tier defines domain standards that provide structural and semantic stability for Application Profiles. The upper tier holds the design and documentation components of specific metadata applications.

Taking the upper tier of the Singapore Framework as a roadmap, the sections that follow walk through the process of creating a DCAP. To illustrate the process we create a simple application profile that describes books and authors. We call this example MyBookCase.

3. Defining Functional requirements

The purpose of any metadata is to support an activity. Defining clear goals for the application used in that activity is an essential first step.

Functional requirements guide the development of the application profile by providing goals and boundaries and are an essential component of a successful application profile development process. This development is often a broad community task and may involve managers of services, experts in the materials being used, application developers, and potential end-users of the services.

There are methodologies to help in the creation of functional requirements, such as business process modeling, and methods for visualizing requirements, such as the Unified Modeling Language [UML]. Some find that the definition of use cases and scenarios for a particular application helps elicit functional requirements that might otherwise be overlooked.

Functional requirements answer questions such as:

- What do you want to accomplish with your application?

- What are the limits of your application? What will it not attempt to do?

- How do you want the application you create to serve your users?

- Will your application need to perform specific actions, such as sorting, or downloading data in particular formats?

- What are the key characteristics of your resources, and how does this affect your selection of data elements? For example, do you need to handle a variety of character sets?

- What are the key characteristics of your users? Are they associated with a particular institution or are you serving a general public? Do they all speak the same language? How expert are they in relation to the data your application will manage? How expert are they about the type of resources described?

- Are there existing community standards that need to be considered?

Functional requirements can include general goals as well as specific tasks that you need to address. Ideally, functional requirements should address the needs of metadata creators, resource users, and application developers so that the resulting application fully supports the needs of the community.

These are some sample requirements from the Scholarly Works Application Profile (SWAP) [SWAP]:

Facilitate identification of open access materials.

Enable identification of the research funder and project code.

A set of functional requirements may include user tasks that must be supported such as the following from the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) [FRBR]:

Use the data to find materials that correspond to the user's stated search criteria.

Use the data retrieved to identify an entity.

For the MyBookCase DCAP our functional requirements are:

Use the data to retrieve books with a title search.

Limit a search to a particular language.

Sort retrieved items by publication date.

Find items about a given subject.

Provide the author's name and email address for contact purposes.

4. Selecting or Developing a Domain model

After defining functional requirements, the next step is to select or develop a domain model. A domain model is a description of what things your metadata will describe, and the relationships between those things. The domain model is the basic blueprint for the construction of the application profile.

The domain model for MyBookCase has two things: Books and Persons (the authors of the books). We will see below how to describe the book using elements such as title and language , and to describe the Person with a name and email address. The domain model for our MyBookCase is simply:

Models can be even simpler than this (e.g., just Book ) or they can be more complex. The domain model for the Scholarly Works Dublin Core™ Application Profile, for example, is based on the library community's domain model: Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records (FRBR) [FRBR]. SWAP defines Scholarly Work in place of FRBR's more general entity Work and introduces new agent relationships beyond those in FRBR, such as isFundedBy and isSupervisedBy. In this way, SWAP makes use of FRBR but customizes the FRBR model to meet its specific needs:

5. Selecting or Defining Metadata Terms

After we have defined the domain model for our metadata, we need to choose properties for describing the things in that model. For example, a Book can have a title and author. The author will be a Person with a name and an email address

The next step, then, is to scan available RDF vocabularies to see whether the properties needed have already been declared and are available for use. Using existing properties, when appropriate, requires less effort and increases the interoperability of your metadata. If the properties one needs are not already available, it is possible to declare one's own, as described in Appendix C.

For the purposes of our simple example, the DCMI Metadata Terms [DCMI-MT] is a source of properties for basic resource description. A more extensive set of properties, directly related to FRBR, is under development for the Resource Description and Access (RDA) standard [RDA_ELEMENTS][RDA_ROLES]. The "Friend of a Friend" vocabulary has useful properties for describing people [FOAF].

The most obvious consideration in evaluating terms from existing vocabularies is their definition. The Dublin Core™ property "title", for example, is defined as "a name given to the resource". If the definition fits your needs, this property is a candidate for use in your profile. However, the suitability of a property for use in a particular application also depends on the type of values the property can have. The types of values intended for your properties must match the allowed value types of the existing properties you wish to use.

You may find it useful to ask the following questions about the values you intend to use with each of the properties needed in the profile. Note that for any given property, there may be more than one "yes" answer.

-

Do you want to use free text for the value of the property?

-

Will the free text need to follow a pre-defined format such as the W3C format for dates ("YYYY-MM-DD")?

-

Will you want to select valid values from a controlled list?

- If so, is that list already available somewhere, or will you need to create it?

- Do you want to limit the valid values to a selection from a list, or can unlisted values be used?

- Have the values in the list been assigned identifiers (in the form of URIs)? Or do you anticipate that URIs could be available for them at a future date?

-

Will single value strings suffice (e.g., "1989" or "John Adams") or is there potentially a need for more complex descriptive structures with multiple components, as when an author is described with a name , email address , and affiliation?

Looking again at our MyBookCase , this is how we might answer the questions about the properties for book:

- The title will be transcribed from the book itself. It will be a free text string.

- We want to use the date property in various ways in our software application, such as sorting a set of retrieved bibliographic records, so we want to be sure that dates are presented in a uniform way as a structured string.

- We want to indicate the language of the book so that users can limit their searches by language. To make sure that languages are always input in the same way, we want to use a controlled list of languages.

- We want to record the subject from a controlled list. At least one possible controlled list, the Library of Congress Subject Headings, is available to us with URIs identifying the vocabulary values [LCSH].

- We know that our author is not a single text string but will be described with several pieces of information, such as name and email address.

The metadata development process will use these decisions to create the technical model of the data elements as described in Appendix C. This analysis results in the following data model, which is consistent with RDF and the DCMI Abstract Model:

title

For title we can use the Dublin Core™ property

dcterms:title, which can take a free text string (a "literal").

date Because we want to perform

automated operations like sorting on the date,

we can select the Dublin Core™ property dcterms:date.

This property can take a string value. We can indicate that

the value string is formatted in accordance with the W3C

Date and Time Formats specification by using syntax encoding

scheme dcterms:W3CDTF.

language

The language needs to be selected from a controlled list.

We achieve this by requiring the use of

three-letter codes listed in the international standard ISO

639-3 for the representation of names of languages (such as

"eng" for "English") together with the syntax encoding scheme

dcterms:ISO639-3 as a datatype. For this, we can use

the DCMI property dcterms:language, which can accommodate

either an identifier for the language term or a string.

subject

We want to record the subject using a

controlled list. Rather than create our own, it is less work

to make use of a list that already exists, and this also

increases the potential for interoperability for our data. We

decide that the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)

meet our needs. Because the terms in LCSH are

available as a formal vocabulary using the RDF vocabulary

Simple Knowledge Organization System [SKOS],

we have the option to indicate each subject by using the URI

that identifies it. For example, the Library of Congress

subject heading "Islam and Science" has been assigned the URI

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/sh85068424. The DCMI property

dcterms:subject can support the use of plain strings or a URI.

author

Because our author needs to be

described with multiple components, such as name and email

address, the author property will need to have a

non-literal range so that a separate but linked description can

be created in the metadata record. The Dublin Core™ property

dcterms:creator can be used with a non-literal

value, so we will use this in MyBookCase.

The selection of properties for describing the

author as a person follows the same

model:

These decisions are summarized in the table below, which reflects the technical analysis of the properties that is described in Appendix C. The column header terms are defined in the Dublin Core™ Abstract model [DCAM].

| Property | Range | Value String | SES URI | Value URI | VES URI | Related description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dcterms:title | literal | YES | no | not applicable [1] | not applicable | not applicable |

| dcterms:created | literal | YES | YES [2] | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| dcterms:language | non-literal | YES | YES [3] | no | no | no |

| dcterms:subject | non-literal | YES | no | YES | YES [4] | no |

| dcterms:creator | non-literal | YES | no | no | no | YES |

| foaf:firstName | literal | YES | no | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| foaf:family_name | literal | YES | no | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| foaf:mbox | non-literal | no | no | YES [5] | no | no |

[1] These values are not applicable for values with a "literal" range.

[2] http://purl.org/dc/terms/W3CDTF

[3] http://purl.org/dc/terms/ISO639-2

[4] http://purl.org/dc/terms/LCSH

[5] Email addresses can be given using mailto: URIs.

6. Designing the Metadata Record with a Description Set Profile

The next step is to describe the metadata record in detail.

In the DCMI approach, a metadata record is based on the

Description Set Model (itself part of the DCMI Abstract Model

DCAM (see Appendix

A), and the record's design is detailed in a Description

Set Profile (or DSP) using a DSP constraint language [DSP]. For each Description and Statement

in a record, the DSP defines a template, and each

template holds relevant constraints specifying

technical details such as the repeatability of elements or

restrictions on allowable values. This section presents a simple

Description Set Profile for MyBookCase.

A DSP contains one Description Template for each

thing in the domain model, which in turn contain

statement templates for all of the properties that describe the

thing. These templates also define any rules that constrain the

use of the description or the properties, such as value types or

requirements and repeatability.

The DSP for MyBookCase will have two Description Templates:

one for Book and one for Person. Each Description Template

has a Statement Template for each of the properties used to

describe the Book or Person. A statement template names the property and contains all the constraints on

the property, value strings, vocabulary encoding schemes, etc. that

apply to a single kind of statement.

If we decide that each metadata record is to represent exactly one book, then a

book Description Template will occur once and only once in each Description Set:

DescriptionSet: MyBookCase Description template: Book minimum = 1; maximum = 1

We can decide that each Book must have one (and only one)

title, which is identified with the property URI

http://purl.org/dc/terms/title.

Statement Templates

are also created for each of the other properties used to describe

a Book (with occurrence options and other constraints as

needed):

DescriptionSet: MyBookCase

Description template: Book

minimum = 1; maximum = 1

Statement template: title

minimum = 1; maximum = 1

Property: http://purl.org/dc/terms/title

Type of Value = "literal"

Statement template: dateCreated

minimum = 0; maximum = 1

Property: http://purl.org/dc/terms/created

Type of Value = "literal"

Syntax Encoding Scheme URI = http://purl.org/dc/terms/W3CDTF

Statement template: language

minimum = 0; maximum = 3

Property: http://purl.org/dc/terms/language

Type of Value = "non-literal"

takes list = yes

Syntax Encoding Scheme URI = http://purl.org/dc/terms/ISO639-2

Statement template: subject

minimum = 0; maximum = unlimited

Property: http://purl.org/dc/terms/LCSH

Type of Value = "non-literal"

takes list = yes

Value Encoding Scheme URI = http://lcsh.info/

Statement template: author

minimum = 0; maximum = 5

Property: http://purl.org/dc/terms/creator

Type of Value = "non-literal"

defined as = person

Some of the above properties have a minimum

occurrence of 0 (zero). This is a way of saying that

these properties are optional in our record and that a record is valid even if these properties are not present.

Some of the properties are repeatable, such as language, which can

occur as many as three times, and author, which can occur

as many as five times. We've defined the author as having the

value of Person, which is described in its own Description

Template:

Description template: Person id=person

minimum = 0; maximum = unlimited

Statement template: givenName

Property: http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/givenname

minimum = 0; maximum = 1

Type of Value = "literal"

Statement template: familyName

Property: http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/family_name

minimum = 0; maximum = 1

Type of Value = "literal"

Statement template: email

Property: http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/mbox

minimum = 0; maximum = unlimited

Type of Value = "non-literal"

value URI = mandatory

A given Person can have one optional given name and one

optional family name, each of which are literal strings. A

Person can also have an email address which must be represented

by a URI with the prefix mailto:. Because many of us have more

than one email address, we allow this statement to repeat

as often as necessary.

We allow our Person description template to be used any number of times in the

metadata record. This may seem to conflict with the fact that

Person can only be used to represent an author up to five times in the

Book description, but we anticipate other possible uses for

Person in our record, such as subjects of a book, so we have

chosen not to limit its number in the record in general.

Note that each Person description contains data elements

for only one person. This also means that an author

statement will have only one Person value. If there are two

authors, then two author statements will be needed in

the metadata record, each representing one person. One might allow a single person to have more than one name,

such as real names and pseudonyms; however, the metadata would

clearly distinguish the case of multiple authors (multiple

Description Templates) from that of a single author with

multiple names (multiple Statement Templates).

If you wish to include an affiliated institution for the

author, you may want to create an institution

Description Template that contains the name and location of that

institution, which will then link to the author

Description Template. You may also have other uses for corporate

names and locations such as for recording information about

the publisher of the book.

This completes the simple Description Set Profile for

MyBookCase; see Appendix B for a version

of this DSP encoded in XML.

7. Usage Guidelines

A Description Set Profile defines the "what" of the

application profile; usage guidelines provide the "how" and

"why". Usage guidelines offer instructions to those

who will create the metadata records. Ideally, they

explain each property and anticipate the decisions that

must be made in the course of creating a metadata record.

Documentation for metadata creators presents some of the

same information that is included in the DSP, but in a more

human-understandable form. Those inputting metadata will need

to know: is this property required? is it repeatable? am I limited

in the values that I can use with the property? Oftentimes

a user interface can answer these questions, for example by

presenting the metadata creator with a list of valid values

from which to choose.

Some examples of the kinds of rules that might appear in usage guidelines are:

- For works of multiple authorship, the order of authors and how many to include (e.g. "the first three", or "no more than twenty")

- How to interpret the prescribed vocabulary of document types

- The minimum required elements for a "minimal" record

- Character sets, punctuation, and abbreviations to be used in strings

In some cases where usage guidelines are relatively simple, they may be included

in the DSP document with the description of the property. The Scholarly Works

Application Profile is an example

where guidance instructions are included alongside the

the Description Set Profile definition.

Other communities may have highly complex rules which,

due to their length and complexity, are

best presented as separate documents.

For example, the Anglo-American Cataloguing

Rules used as guidelines by some libraries are recorded in

a 600-page book [AACR2]. Instructions

relating to titles appear in many of its chapters,

cover many pages of text. Guidelines of this length may best be

presented separately from the DSP.

8. Syntax Guidelines

The technologies described in this document are syntax

neutral; that is, they do not require any particular

machine-readable encoding syntax as long as the syntax employed

can fully express the values and relationships defined in

the DCAP.

To help developers turn their application profiles into

functioning software applications, DCMI has developed various encoding

guidelines [DCMI-ENCODINGS].

Description Set Profiles can be deployed using any concrete

implementation syntax for which a mapping to the abstract

model has been specified. DCMI has developed or is developing

guidelines for encoding DCAM-based metadata in HTML/XHTML,

XML, and RDF/XML; others could be added in the future. There

is no restriction on use of other types of syntax as long as

the resulting data format is compatible with the foundation

standards and with the DCMI Abstract Model.

References

AACR2

American Library Association and Library Association, Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd ed. (London: Library Association, 1978).

CTERMS

Dublin Core™ Collection Description Terms.

<http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/collection-description/collection-terms/2007-03-09/>

See also RDF schema <

http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/collection-description/collection-terms/2007-03-09/cldterms.rdf>

COOLURIS

Sauermann, Leo, Richard Cyganiak, eds. Cool URIs for the Semantic Web.

<http://www.w3.org/TR/cooluris/

DCMI-ENCODINGS

DCMI Encoding Guidelines

<http://dublincore.org/schemas/>

DCMI-MT

DCMI Metadata Terms. January, 2008.

<http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/dcmi-terms/>

See also RDF schema <http://dublincore.org/2008/01/14/dcterms.rdf>

Powell, Andy, Mikael Nilsson, Ambjoern Naeve, Pete Johnston and Thomas

Baker. DCMI Abstract Model. DCMI Recommendation. June 2007.

<http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/abstract-model/2007-06-04/>

Nilsson, Mikael, Thomas Baker, Pete Johnston. The Singapore Framework for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles.

<http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/singapore-framework/2008-01-14/>

Nilsson, Mikael. Description Set Profiles: A constraint language for Dublin Core™ Application Profiles. March, 2008.

<http://dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/dc-dsp/2008-03-31/>

ETERMS

Eprints Terms.

<http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/repositories/digirep/index/Eprints_Terms>

Brickley, Dan, Libby Miller. FOAF Vocabulary Specification 0.91. November, 2007

<http://xmlns.com/foaf/spec/>

IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records.

(1998). Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records - Final Report.

Munich: K.G. Saur. Also available at

<http://www.ifla.org/VII/s13/frbr/index.htm>

Library of Congress Subject Headings. In: Library of Congress Authorities and Vocabularies.

<http://id.loc.gov/authorities>

Linked Data

<http://linkeddata.org>

RDA-ELEMENTS

<http://metadataregistry.org/schema/show/id/1.html>

RDA-ELEMENTS

<http://metadataregistry.org/schema/show/id/4.html>

RDF

World Wide Web Consortium. Resource Description Framework

(RDF) <http://www.w3.org/RDF>

Brickley, Dan and R.V. Guha, editors. RDF Vocabulary Description Language

1.0: RDF Schema. W3C Recommendation. 10 February 2004.

<http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-schema/>

Manola, Frank, Eric Miller. RDF Primer. W3C Recommendation 10 February 2004.

<http://www.w3.org/TR/2004/REC-rdf-primer-20040210/>

RECIPES

Berrueta, Diego, Jon Phipps, eds. Best Practice Recipes for Publishing RDF Vocabularies.

<http://www.w3.org/TR/swbp-vocab-pub/>

RFC3066

Alvestrand, H. Tags for the Identification of Languages. January, 2001.

<http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3066.txt>

SWAP

Scholarly Works Application Profile.

<http://www.ukoln.ac.uk/repositories/digirep/index/Eprints_Application_Profile>

UML

Booch, Grady, James Rumbaugh and Ivar Jacobson. The Unified Modeling Language

User Guide. Addison-Wesley, 1998.

Appendix A: Description Set Model (from DCMI Abstract Model)

According to the "Description Set Model" of the DCMI Abstract Model

[DCAM], a Dublin Core™ description set has the following structure:

- a description set is made up of one or more descriptions

- a description is made up of

- zero or one described resource URI and

- one or more statements

- a statement is made up of

- exactly one property URI and

- exactly one value surrogate

- a value surrogate is either a literal value surrogate or a non-literal value surrogate

- a literal value surrogate is made up of

- exactly one value string

- a non-literal value surrogate is made up of

- zero or one value URIs

- zero or one vocabulary encoding scheme URIs

- zero or more value strings

- a literal value surrogate is made up of

- a value string is either a plain value string or a typed value string

- a plain value string may be associated with a value string language

- a typed value string is associated with a syntax encoding scheme URI

- a non-literal value may be described by another description.

Appendix B: MyBookCase Description Set Profile

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<DescriptionSetTemplate xmlns="http://dublincore.org/xml/dc-dsp/2008/01/14"

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://dublincore.org/xml/dc-dsp/2008/01/14">

<DescriptionTemplate ID="Book" minOccurs="1" maxOccurs="1" standalone="yes">

<StatementTemplate ID="title" minOccurs="1" maxOccurs="1" type="literal">

<Property>http://purl.org/dc/terms/title</Property>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="dateCreated" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="1" type="literal">

<Property>http://purl.org/dc/terms/created</Property>

<LiteralConstraint>

<SyntaxEncodingScheme>http://purl.org/dc/terms/W3CDTF</SyntaxEncodingScheme>

</LiteralConstraint>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="language" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="3" type="nonliteral">

<Property>http://purl.org/dc/terms/language</Property>

<NonLiteralConstraint>

<VocabularyEncodingSchemeURI>http://purl.org/dc/terms/ISO639-3</VocabularyEncodingSchemeURI>

<ValueStringConstraint minOccurs="1" maxOccurs="1"/>

</NonLiteralConstraint>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="subject" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="infinite" type="nonliteral">

<Property>http://purl.org/dc/terms/LCSH</Property>

<NonLiteralConstraint>

<VocabularyEncodingSchemeURI>http://lcsh.info</VocabularyEncodingSchemeURI>

<ValueStringConstraint minOccurs="1" maxOccurs="1"/>

</NonLiteralConstraint>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="author" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="5" type="nonliteral">

<Property>http://purl.org/dc/terms/creator</Property>

<NonLiteralConstraint descriptionTemplateRef="person"/>

</StatementTemplate>

</DescriptionTemplate>

<DescriptionTemplate ID="person" minOccurs="0" standalone="no">

<StatementTemplate ID="givenName" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="1" type="literal">

<Property>http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/givenname</Property>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="familyName" minOccurs="0" maxOccurs="1" type="literal">

<Property>http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/family_name</Property>

</StatementTemplate>

<StatementTemplate ID="email" minOccurs="0" type="nonliteral">

<Property>http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/mbox</Property>

<NonLiteralConstraint>

<ValueURIOccurrence>mandatory</ValueURIOccurrence>

</NonLiteralConstraint>

</StatementTemplate>

</DescriptionTemplate>

</DescriptionSetTemplate>

Appendix C: Using RDF properties in profiles: a technical primer

Every application profile design team should include members

who understand basic principles for designing metadata on

the basis of RDF. This section provides a brief overview

of the modeling choices involved in the selection and use

of RDF properties in application profiles. The section

concludes by relating the technical design choices to the

property-by-property requirements with regard to:

- Whether free text will be used,

- Whether the free text will ever need follow a pre-defined format,

- Whether valid values should be selected from a controlled list, and

- Whether single strings will suffice or more complex values are needed.

The basics of RDF properties

RDF properties are designed to be referenced and processed

in a consistent way independently of the contexts in which

they appear. The Dublin Core™ element title,

for example, can be used in one context for describing books

and in another for describing statues. When used correctly

and in accordance with the RDF "grammar" for data, such

globally defined vocabularies provide a basis for integrating

resource descriptions from a variety of sources into coherent

data aggregations.

In order to be usable in RDF-based metadata, properties

must be identified with Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs).

The Dublin Core™ element title, for example, is

identified with the URI http://purl.org/dc/terms/title

(abbreviated here as dcterms:title). Good practice

dictates that these URIs be declared and documented somewhere

as "RDF properties". This declaration may be made in prose

but typically is also made in a machine-readable RDF schema

and ideally by the owner of the Internet domain or sub-domain

used for the URIs. The URI for dcterms:title,

for example, resolves (by redirection) to an RDF schema—

http://dublincore.org/2008/01/14/dcterms.rdf at the

time of writing—which says in a machine-understandable way

that dcterms:title is an RDF property. The subdomain

http://purl.org/dc/ is "owned" (in the sense of

"controlled") by the organization Dublin Core™ Metadata

Initiative.

In designing a metadata application, it is for many

reasons desirable to use RDF properties that have already been

declared somewhere. At a minimum, this is easier than doing

the extra work involved in declaring one's own RDF properties.

More importantly, the use of known properties provides a basis

for semantic interoperability with metadata from other sources.

Bear in mind that individuals who create vocabularies may

change jobs and move on; research projects finish their work

and eventually their servers disappear; and ownership of domain

names may lapse, so that URIs which resolve today to an RDF

schema might ten years from now resolve to shoe advertisements.

It is best to use properties backed by organizations that

have made a commitment to their maintenance.

RDF property semantics

RDF properties are usually provided with natural-language

definitions. Designers of application profiles should take

care to use the properties in ways that are compatible with

these definitions. Designers may add technical constraints

on use of properties (such as repeatability), or provide more

narrow interpretations of definitions for particular purposes,

but they should not contradict the meaning of the properties

intended by their maintainers.

The intended meaning of a property is determined not just

by natural-language definitions but also by formally declared

relationships of the given property to other properties.

Definitions typically specify a formal "domain" (the

class of things that can be described by the property)

and a "range" (a class of things that can be values).

This additional information improves the utility of RDF

properties by enabling inferences about the things they

are used to describe. The property foaf:img

(image), for example, has a domain of

foaf:Person and a range of foaf:Image,

so that when metadata-consuming applications find metadata

using the property foaf:img, they can automatically

infer that the thing being described with this property is a

person and that the value being referred to by the property

is an image. Properties may also be semantic refinements of

other properties. The property dcterms:abstract, for

example, is a sub-property of dcterms:description,

meaning that anything which is said to have an abstract also

may be said to have a description.

For the purposes of re-using properties in application

profiles, it is especially important to check whether or

not the properties are intended to be used with values

that are literals. Properties that are intended to be used

with values that are literals—i.e., with values that by

definition may consist of just one value string, optionally

augmented with a language tag (in a "plain value string")

or a datatype identifier (in a "typed value string")—

are said to have a "literal" range. Examples of

properties with a "literal" range are dcterms:date,

which is declared with a range of rdfs:Literal,

and foaf:firstName, which is defined as being an

owl:DatatypeProperty. The advantage of properties

with a "literal" range is simplicity. The metadata carries—

and metadata-consuming applications expect—just one plain

or typed value string, making the metadata simple to encode

and simple to process.

Properties with anything other than a "literal" range are

said to have a "non-literal" range. Examples of properties

with a "non-literal" range include dcterms:license,

with the range dcterms:LicenseDocument,

and foaf:holdsAccount, with the range

foaf:OnlineAccount. Where literal-range properties

may be simpler to process, non-literal-range properties are

more flexible and extensible. In descriptive metadata, literal

values constitute "terminals" (in the sense of "end point");

the value string "Mary Jones" cannot itself be the starting

point for any further description of the person Mary Jones.

A non-literal value, in contrast, has hooks to which one

may attach any number of additional pieces of information

about the person Mary Jones, such as her email address,

institutional affiliation, and date of birth. Potentially,

non-literal values can be represented by any combination of

the following:

- A plain or typed value string (Value String in the DCMI Abstract Model)—and not just one, but potentially several in parallel, as in the case of a title rendered in English, French, and Japanese.

- A URI identifying the value resource (Value URI).

- A URI identifying an enumerated set (or controlled vocabulary) of which the value is a member (Vocabulary Encoding Scheme URI).

Note that the difference between literal-range and

non-literal-range properties is primarily a modeling issue.

The type of property determines how the metadata will be

encoded machine-processably for exchange and interpreted by

applications that consume the metadata. End-users need not

necessarily see the difference. When displayed in a search

result, a value string looks the same regardless of whether

it is directly a literal value or a value string attached to

a non-literal value.

When using an existing property, the choice between a

literal and non-literal range will usually be mandated by

the official definition. If that mandated choice is not

sufficient (e.g., the dcterms:date property has a

literal range and a more complex value is needed), or if a

property with the needed semantics cannot be found anywhere,

then a new property (with a new URI) must be coined.

Coining new RDF properties

By definition, Dublin Core™ application profiles "use"

properties that have been defined somewhere—i.e., somewhere

outside of the profile itself. If no existing property can

be found among any of the well-known vocabularies, then the

designers of an application profile will need to declare

one themselves.

Declaring a new property is in itself not a difficult task.

One gives it a name, formulates a definition, decides whether

it takes a literal or non-literal range, and coins a URI

for the property under a namespace to which one has access

(and not, for example, under http://microsoft.com

or http://amazon.de). Services such as

http://purl.org, which is used for identifying DCMI

properties, provide "persistent" URIs that can be redirected

to documentation at more temporary locations. Guidance for

creating and publishing RDF vocabularies can be found in "Cool

URIs for the Semantic Web" [COOLURIS],

the RDF Primer [RDF-PRIMER], and

"Best Practice Recipes for Publishing RDF Vocabularies" [RECIPES]. Best-practice examples include

DCMI Metadata Terms [DCMI-MT],

Dublin Core™ Collection Description Terms [CTERMS], and Eprints Terms [ETERMS], It is good practice for terms also

to be published in RDF schemas; for examples, see see the schemas associated

with DCMI Metadata Terms [DCMI-MT]

and Dublin Core™ Collection Description Terms [CTERMS].

Whether to assign a literal or a non-literal range is

essentially a choice between simplicity and extensibility.

Value strings alone may suffice for recording a date

("2008-10-31") or a title ("Gone with the Wind"), but for

authors, one may need to record more than just a name.

When in doubt, it is wise to assign a non-literal range.

In the case of authors, for example, the non-literal range

provides a hook for adding email address, affiliation, and date

of birth or for using a URI to point to a description of the

author somewhere outside one's own application. Because they

support the use of URIs (i.e., the use of URIs "as URIs"

and not just "as strings"), non-literal values are crucial

in achieving the ideal of linked metadata—descriptions

that are cross-referenced using globally valid identifiers.

Translating user-defined data requirements into design decisions

We can now return to the questions asked of data content

experts about each potential property with regard to potential

values.

Do you want to use free text? "Free text" (i.e.,

strings of characters) is called a Value String in the

DCMI Abstract Model and can be used with properties of either

a literal or non-literal range. Note that in some cases,

there may be a requirement to use multiple value strings,

in parallel, in a single statement, for example in the

case of values that are represented in multiple languages.

This can only be done in conjunction with non-literal-range

properties.

Will the free text ever need to follow a pre-defined

format? If so, then the Value String can be used

with a Syntax Encoding Scheme (datatype).

Will single value strings suffice or is there a need

(or potential need) for a more complex structure with multiple

components? If anything more than a single value string

is needed for the value, then the property used must have a

non-literal range. If by chance you have found a property with

the right natural-language definition but the wrong range—

for example, with the more limiting literal range—you may

need to coin your own property, with its own URI, using that

definition with a non-literal range.

Might you ever want to use a URI to identify the value

or point to a description of the value? The DCMI Abstract

Model defines a Value URI as a syntactic construct

separate from a Value String. Value URIs cannot

be used to describe literal values; they must be used with

properties that have a non-literal range. It is of course

possible to record a URI as a Value String—a URI is,

after all, a string—but applications consuming the metadata

on this basis will have no reliable way to distinguish that

string from other strings in order to interpret it

as an identifier.

Will you want to select valid values from a controlled

list? If so, then the following are possible:

- Simple lists of text strings may be informally documented as usage guidelines in a Description Set Profile.

- Simple lists of text strings may be more formally defined as a Syntax Encoding Scheme (SES, or datatype), with a URI, making the list citable and available for use in many application profiles.

- A list of strings may be interpreted as labels for a list of concepts. This is called a Vocabulary Encoding Scheme (VES). Note that in contrast to the individual text strings listed in an SES, the individual concepts of a VES may also, or alternatively, be identified using URIs.

- If the list of values is already available somewhere and has already been identified (e.g., by DCMI) as a Syntax Encoding Scheme or Vocabulary Encoding Scheme, then use that URI with the proper modeling construct.

- If the list of values is already available somewhere but has not yet been identified as an SES or VES, you may need to interpret which model it more closely fits. Sometimes either interpretation is defensible. Whichever way you decide, it is important that the URI you coin for the encoding scheme be clearly declared as one or the other in order to avoid any ambiguity in the metadata.

- If you want to restrict the set of valid values to a fixed list (as opposed to allowing the use of unlisted values), this restriction can be declared and documented in a Description Set Profile.

In general, the use of formally defined values,

such as controlled lists, adds precision to metadata and

thus increases its suitability for automatic processing.

The use of SES and VES, as appropriate, is an important

step in this direction. Increasingly, however, URIs

are being assigned to individual terms in controlled

vocabularies using the RDF vocabulary Simple Knowledge

Organization System [SKOS]. The concept

"World Wide Web" in the Library of Congress Subject

Headings, for example, has recently been assigned the URI

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/sh95000541#concept. As controlled

vocabularies become increasingly "SKOSified", it will become

easier to use those vocabularies to find and integrate

access to resources from multiple sources on the open Web.

The VES construct can flexibly accommodate the transition

from Value Strings alone, to Value Strings

with VES URIs, and from there to Value URIs

(with or without VES URIs).